(Business in Cameroon) – As of April 30, 2025, the Caisse de Dépôts et Consignations (CDEC) had received only CFA83 billion, according to Investir au Cameroun. This amount represents just 21 % of the CFA400 billion it aims to centralize for the year. Nearly CFA317 billion meant for its portfolio remain held by public and private entities. The CDEC views these delays as reluctance, or even a lack of compliance, from some actors required to transfer these funds.

Banks at the center but still reluctant

The banking sector accounts for most of the unmet transfers. The team of Richard Evina Obam, the CDEC’s director general, expects CFA250 billion in transfers from banks in 2025. So far, only CFA44 billion have been sent. About CFA206 billion are missing, or nearly 82 % of what is expected from the sector.

The current transfer effort is concentrated among a few major institutions. BICEC leads with CFA13 billion already transferred, followed by SCB (CFA8 billion), Société Générale Cameroun (CFA7 billion), and Standard Bank (CFA6 billion). These four banks provide most of the funds already sent to the CDEC, confirming the key role of large financial institutions in achieving the mechanism’s goals.

A second group of institutions also contributes, though at lower levels. Bange Bank Cameroon, UBC, and UNICS have each sent CFA1 billion. Afriland First Bank and Crédit Foncier du Cameroun follow with CFA900 million and CFA910 million respectively. Next are NFC Bank (CFA473 million), UBA (CFA673 million), Citibank (CFA600 million), and Ecobank Cameroun and La Régionale (CFA327 million each). These medium-sized banks are participating, but their contributions remain far from the overall targets.

At the lower end, some transfers are small but reflect initial compliance. CCA–Crédit Communautaire d’Afrique has sent CFA120 million, while BGFIBank has transferred just CFA42 million. These low amounts highlight the still limited engagement of several institutions.

Afriland First Bank at the heart of the standoff

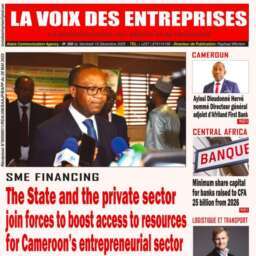

To accelerate the process, the CDEC has opted for a tougher stance with the institutions considered most resistant. According to information published by Investir au Cameroun, it is demanding that Afriland First Bank transfer more than CFA166 billion in public deposits, consignments, and judicial escrow accounts held by the country’s largest bank. If the transfer is not made voluntarily, the CDEC is threatening forced recovery measures, including collection notices, targeted asset seizures, and on-site inspections to verify the accounts involved.

The case is sensitive because it targets a systemic actor. As of December 31, 2024, Afriland First Bank held CFA1 557 billion in deposits and nearly 23 % of the credit market. By taking on such a major institution, the CDEC aims to send a message to the whole sector: funds legally assigned to the CDEC must be centralized, even if that requires legal action.

At the same time, the institution is preparing to create its own banking subsidiary to better collect and manage the public funds it is entitled to, and to reduce its operational dependence on commercial banks.

Beyond banking, other entities are beginning to comply. The Société Immobilière du Cameroun (SIC) transferred CFA482 million in February 2025 for housing guarantees from active and inactive clients. Additional transfers from insurance companies, the Treasury, bailiffs, and microfinance institutions complete the CFA83 billion received by the CDEC by April 30. It remains to be seen whether the main laggards will meet the year-end deadline.

Ultimately, this issue goes beyond amounts due, touching on the governance of public deposits and the balance of power among the regional regulator, the state, and the CDEC.

Cobac, CDEC, Minfi: a triangle of tensions

The CDEC’s offensive has triggered strong opposition from the Central African Banking Commission (Cobac), the supervisory authority for banks in CEMAC countries. In a letter to the Finance Minister, Cobac criticized the CDEC’s “seizures” and threats of legal action against several credit and payment institutions, arguing they could undermine public confidence and bypass the recently adopted regional framework for handling inactive accounts and unclaimed assets. The Commission stressed that new UMAC-CEMAC regulations strictly define how these funds must be transferred to deposit agencies and urged the minister, as monetary authority and CDEC supervisor, to halt actions that deviate from these rules.

In its response, the CDEC accused Cobac of contradictions and openly criticized “non-compliant banks” for resisting so they could continue benefiting from public resources assigned to the CDEC since the April 2008 law. It accused the regional regulator of siding with these banks, overstepping its authority by interfering in Cameroon’s public procurement guarantee system, and even denounced what it called “regulator capture.”

Caught between these opposing positions, the Ministry of Finance maintains ambiguity, even though it has already transferred the funds owed by the Treasury to the CDEC. To settle an outstanding amount estimated at CFA40–60 billion, the ministry agreed with the national branch of the central bank to automatically debit CFA2 billion per month for the CDEC.

Although officially responsible for upholding regional commitments, the ministry is allowing the dispute among the CDEC, Cobac, and Afriland to persist, potentially delaying the transfer schedule the state says it wants to accelerate. The director general argues that Cobac should respect the principle of special competence and refocus on its core mandate as an objective regulator of the banking sector. He maintains that “the legal immunity sought by non-compliant banks under Cobac’s protection cannot override the law.”

Contrary to concerns that the CDEC’s actions could destabilize the financial system, the director general argues that real risks to CEMAC’s financial stability come from non-compliance with rules, questionable arrangements, compromises among actors, and weak sanctions. Under the law, Article 55 of the 2011 decree requires the Finance Minister to ensure the full transfer of funds allocated to the CDEC within six months after the appointment of its leadership. Ultimately, it is up to the Cameroonian government to decide between regional orthodoxy, the CDEC’s demands, and the interests of a banking sector that plays a central role in financing the national economy.